Listeria and Pregnancy

Being diagnosed with Listeria when you are pregnant is very frightening.

We are here to answer questions and provide information about Listeria infections in moms and babies.

A Listeria infection diagnosis (listeriosis) while pregnant immediately puts you and your baby among the highest risk categories.

But, you did nothing wrong. Listeria almost always comes from contaminated food and is undetectable to the person eating it.

You will likely need immediate medical care as well as care throughout your pregnancy

The hospitalization rate for a typical Listeria monocytogenes outbreak is more than 90% and pregnant women account for 27% of all listeriosis infections in the U.S.

The risks from listeriosis are substantial, including miscarriage and both fetal and maternal death. Getting immediate high quality hospital care is critical in reducing these risks as much as possible.

The vast majority of people sickened by Listeria get the infection from eating contaminated food. Because this germ is so incredibly dangerous, the U.S. government has zero tolerance for Listeria in any food, in any form. If you caught listeriosis from food, then that food was sold in violation of the law and you may be entitled to compensation for you and your baby

What is Listeria?

Listeria is a type of bacteria. You might also hear it called a “pathogen”. Being a pathogen means that is causes disease. There are 6 common species of Listeria, including Listeria ivanovii and Listeria innocua, but the one that causes the most human illness is called Listeria monocytogenes. There are more than 14 kinds of Listeria monocytogenes bacteria, (called serotypes), but only three of them typically cause disease in humans. If you or your baby have been diagnosed with Listeriosis, it is one of these serotypes that caused your disease.

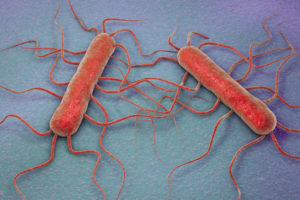

Listeria monocytogenes bacteria

Listeria bacteria are very tiny, about 2 microns long, which means five of them could fit lengthwise across a single red blood cell. They are rod-shaped. You might hear them described as “gram-positive”. This means that that they retain color when tested in a Gram stain procedure and it is an important characteristic for doctors to know as they determine the best way to treat an infection. Listeria bacteria are invisible to the human eye and they do not affect the taste, aroma, texture, or appearance of food. You can’t tell if a food is contaminated with Listeria or any bacteria without a special lab test.

Listeria monocytogenes wasn’t recognized as a major cause of human illness until there were several outbreaks in the United States in the 1980s. The populations that are most affected by this bacteria are the elderly, the very young, people with compromised immune systems, and pregnant women. Listeriosis is a serious risk factor for pregnant women, since this infection can cause miscarriage, stillbirth, premature labor, and infection in the newborn baby.

There aren’t many cases of listeriosis in the United States every year, just about 1,600. But people who are sickened by this pathogen get very sick. The hospitalization rate for a typical Listeria monocytogenes outbreak is more than 90%, and the mortality rate is about 20 to 30%. In just about every Listeria monocytogenes outbreak in the past decade in the U.S., pregnant women have been affected, and fetal loss has occurred. Pregnant women account for 27% of all listeriosis infections in the U.S. If you have been diagnosed with listeriosis, good hospital care and treatment is critical.

Listeria is very hardy. It is one of the toughest pathogens found in food. Unlike most food pathogens, It can grow at refrigerator temperatures, below 40°F, and it can survive freezing temperatures. When Listeria grows into colonies, it can produce a biofilm that protects it against cleaning solvents like soap and even some bleach solutions. It can live in acidic conditions, salty environments, high and low temperatures, and dry environments, but it prefers wet environments. If Listeria is established in a food production or processing facility, especially a place that uses a lot of water, it can be very difficult to eradicate and may persist for years. Listeria can even react to its environment and repair damage to its cell walls caused by antibiotics. The best way to destroy this pathogen is with heat. It will die at temperatures above 165°F.

Because Listeria causes such serious illness, there is zero tolerance for Listeria monocytogenes contamination in ready-to-eat foods in the United States. That means any contamination triggers a recall.

What causes listeriosis?

The Listeria monocytogenes bacteria is widespread in the environment, and is particularly prevalent in soil and water. Listeria monocytogenes bacteria can live in the intestinal tract of animals without sickening them. The bacteria is shed in their feces.

Listeria bacteria have a very long incubation period, which is the time between a person ingesting a pathogen and the development of symptoms. Listeria can incubate in the liver for quite a while before escaping into the bloodstream and causing symptoms. Scientists also think that the Listeria bacteria can move from cell to cell, without passing through the fluid in between, which means it can evade the immune system for a long period of time. That may also explain the long incubation time. Most people don’t start feeling sick until at about one to two weeks after infection, but for some people it might take 2-3 months before they feel sick. This long lag-time can make figuring out what food may have caused the infection (called “trace-back”) very difficult.

Most listeriosis outbreaks are linked to food that has been prepared in some way before being sold, from ice cream to caramel apples to tahini to cut fruit. These foods are typically contaminated in a production or processing facility where Listeria is living on surfaces or elsewhere in the environment.

How do you get a Listeria monocytogenes infection?

Humans get a Listeria infection when they eat food or drink beverages that are contaminated with the bacteria. Most healthy people can fight off this infection while it is still in the liver and never experience any serious symptoms. But, if a person’s health is compromised…or if the patient is a pregnant woman, infection can occur.

The infectious dose of Listeria monocytogenes (how much it takes to make you sick) is not well understood. Scientists do not understand the relationship between the number of Listeria monocytogenes cells in food and the likelihood of developing listeriosis. It could be that low level contamination causes infection in people who are susceptible because of existing health problems.

These processed foods are usually contaminated at the facility that prepares them or at the deli that repackages them. And homemade foods aren’t made with hazard controls most reputable food processors must use.

Deli foods are more susceptible to this contamination because once Listeria is introduced into a facility it can become well established. The pathogen hides in grease traps, drains, slicing equipment, air vents, floor cracks, and food preparation surfaces. Studies have found that retail deli slicer cleaning methods are not effective against this pathogen. The equipment needs to be disassembled for proper cleaning. If a machine is not properly cleaned, and food is sliced and repackaged, it is vulnerable to contamination. And these types of foods are eaten without a “kill step,” or heating to a temperature that destroys the pathogen, so the bacteria survive to make someone sick.

In 2011, a large and deadly Listeria monocytogenes outbreak was linked to Jensen Farms cantaloupe. The fruit was cleaned on used equipment that the FDA cited as a probable factor in the outbreak. A total of 147 people in 28 states were sickened, including seven pregnant women. One mother suffered a miscarriage, and three infants were born with listeriosis. Thirty-three people died.

In 2014, a listeriosis outbreak was linked to prepackaged caramel apples that sickened 35 people in 12 states. Three people died. Eleven pregnant women were sickened in this outbreak. There were three premature births and one fetal loss. In addition, three pediatric cases of Listeria meningitis (swelling around the brain caused by the bacteria) were reported. It turns out that the stick inserted into the apple creates an entry point for Listeria bacteria.

“Because of the particular risk in pregnancy, even though there is zero tolerance for Listeria in food by law, pregnant women are advised to avoid certain foods which may have a higher likelihood of harboring Listeria.”

Any food can be contaminated with this pathogen, including fruits and vegetables, meats, seafood, and even ice cream, but the foods most likely to cause illness or an outbreak are:

|

|

These processed foods are usually contaminated at the facility that prepares them or at the deli that repackages them. And homemade foods aren’t made with hazard controls most reputable food processors must use.

Deli foods are more susceptible to this contamination because once Listeria is introduced into a facility it can become well established. The pathogen hides in grease traps, drains, slicing equipment, air vents, floor cracks, and food preparation surfaces. Studies have found that retail deli slicer cleaning methods are not effective against this pathogen. The equipment needs to be disassembled for proper cleaning. If a machine is not properly cleaned, and food is sliced and repackaged, it is vulnerable to contamination. And these types of foods are eaten without a “kill step,” or heating to a temperature that destroys the pathogen, so the bacteria survive to make someone sick.

In 2011, a large and deadly Listeria monocytogenes outbreak was linked to Jensen Farms cantaloupe. The fruit was cleaned on used equipment that the FDA cited as a probable factor in the outbreak. A total of 147 people in 28 states were sickened, including seven pregnant women. One mother suffered a miscarriage, and three infants were born with listeriosis. Thirty-three people died.

In 2014, a listeriosis outbreak was linked to prepackaged caramel apples that sickened 35 people in 12 states. Three people died. Eleven pregnant women were sickened in this outbreak. There were three premature births and one fetal loss. In addition, three pediatric cases of Listeria meningitis (swelling around the brain caused by the bacteria) were reported. It turns out that the stick inserted into the apple creates an entry point for Listeria bacteria.

How does Listeria infect you?

When you eat food contaminated with Listeria monocytogenes bacteria, it easily survives the low pH of the stomach since it can live in acidic environments. It then moves from your intestines to your liver. The liver in healthy people can destroy this pathogen, but if the immune system is suppressed or if the person is already sick, especially with a chronic illness, the bacteria can grow rapidly and then emerge into the bloodstream.

Pregnant women are also more susceptible because their immune systems are altered in response to growing a baby; as are their unborn babies who lack a developed immune system of their own. If Listeria survives in the liver for long enough, it enters the bloodstream, where it can pass through the blood-brain barrier and infect the brain, the membranes that surround the brain and spinal cord, and the digestive tract. It can also travel to the placenta in pregnant women.

The headache and stiff neck experienced by some patients may be symptoms of Listeria meningitis, since it can infect the meninges (the membrane covering the brain and spinal cord). A high fever is the body’s way of getting rid of the infection by triggering the growth and movement of immune cells.

Pregnant women may only be mildly ill with flu-like symptoms when they are sick with listeriosis. And many women have no symptoms at all or may suffer from diarrhea, stomachache, fever, headaches, and body aches.

Why are pregnant women at more risk for listeriosis?

Studies show that pregnant women are between 10 and 18 times more likely to contract listeriosis than other healthy adults. The pathogen infects otherwise healthy pregnant women who have few or no risk other factors. Scientists are beginning to understand why pregnant women are at high risk for listeriosis during pregnancy: the immune system is suppressed so the embryo isn’t rejected. That makes it easier for bacteria to cause an infection in the body. While the woman’s immune system may be successful at killing some of the pathogen, some may survive, escape into the bloodstream, and travel to the placenta.

In 2015, researchers in Paris discovered a placental breach mechanism for Listeria monocytogenes that may explain why miscarriage, premature labor, and stillbirth are common among pregnant women with this infection.

The placenta is an immunological barrier between the mother and the fetus. That means the pathogens that have reached the placenta are not detected by the mother’s immune system. Listeria bacteria may even invade the lining of the uterus.

The bacteria grow and then “burst” out of the placenta, triggering a miscarriage. This is one theory that was bolstered by research at Berkeley in 2019. The presence of large numbers of pathogens in the placenta may also eventually trigger the mother’s immune system, which causes a miscarriage as a defense mechanism.

Another theory is that the infection in the mother triggers inflammation, which affects the placenta, rendering it unable to protect the fetus. The fetal loss rate due to listeriosis in pregnancy is 20%, and about 3% of newborns die if their mother is infected with this pathogen.

Doctors used to think that the fetus is most susceptible to listeriosis in the third trimester, but new research in 2019 showed that some strains of Listeria may be the cause of many early miscarriages as well.

What are the symptoms of listeriosis?

The main symptoms of listeriosis in non-pregnant women are high fever, stiff neck, serious headache, muscle aches, nausea, and diarrhea. In pregnant women, symptoms may be very mild and are usually similar to the flu. Often, a woman doesn’t even realize she has this infection until something terrible happens to the fetus, or the baby is diagnosed with listeriosis at birth or soon after.

Newborns and infants who are sickened with listeriosis can develop a blood infection, meningitis (inflammation of the membranes around the brain and spinal cord), and respiratory pneumonia. Most newborns who contracted this infection from their mothers are diagnosed a few days to a couple of weeks after birth. Up to 30% of newborns die in spite of antibiotic treatment.

The illness a newborn suffers, along with the onset of symptoms and prognosis, varies depending on whether the illness is early onset or late onset in the pregnancy. Early onset listeriosis cases are usually born premature and can suffer the most serious complications. Up to one-third of newborns who are infected with early-onset listeriosis die. If listeriosis is contracted later in the pregnancy, the infant is usually born full term and healthy. The baby is most likely infected at birth through contact with the mother’s feces or the birth canal during delivery. These infants have a better prognosis than those who are infected with early-onset disease.

How are Listeria cases investigated?

Because Listeria monocytogenes infection is a reportable illness, doctors are required to inform public health officials every time a listeriosis infection is diagnosed. The bacteria’s DNA is read (“sequenced”) using procedures called pulsed field-gel electrophoresis (PFGE) or whole genome sequencing (WGS) to create a “fingerprint”. Isolates from these patients are stored in a national subtyping laboratory called PulseNet. Because most cases of listeriosis occur individually and not in multistate outbreaks, when someone is sickened with this pathogen officials look through years of data to see if another person was sickened with the same bacteria that has the same DNA pattern.

If a match is found between two unrelated people, an outbreak is declared. The same happens if Listeria monocytogenes is found in food. The bacteria will be isolated and studied, then officials look through the PulseNet database to see if any human has been sickened with that particular strain. If food is likely still available for sale, or in consumer’s homes, a recall will usually be initiated. At this point people sickened by Listeria will often contact a food safety law firm, like Pritzker Hageman to recover medical and other costs and make sure the companies who broke food safety laws will not do it again.

The illness onset date in listeriosis outbreaks can extend over years. Patients in listeriosis outbreaks may have been sickened years apart, because the bacteria can survive so long in food processing facilities.

I’m pregnant. How do I know I have listeriosis?

Pregnant women may not know they have listeriosis. If they do show symptoms, these women may naturally think they have a mild case of the flu. Pregnant women suffer from nausea, diarrhea, a mild fever, muscle aches, backache, fatigue, and vomiting. The most common symptom of listeriosis in pregnant women is a fever. And the incubation time in pregnant women before symptoms appear is often longer than in non-pregnant patients (anywhere from 2-10 weeks is common).

The only way to know is to have a test done. A diagnosis is conducted with a blood test or testing a fecal (poop) sample. These tests can only be conducted at a hospital or doctors office and the processing of the tests is done at a medical lab.

It’s important that any pregnant women who has unexplained flu-like symptoms, especially headache, see their doctor as soon as possible. The earlier this infection is diagnosed, the more likely treatment will be effective.

Hispanic women are 24 times more likely to contract listeriosis than non-Hispanic women. Scientists think that the type of cheese consumption that is more common in this population is a risk factor. Queso fresco, panela, quesito casero, and cuajada en hoja are soft cheeses that may be made from unpasteurized milk. Some of these cheeses are homemade, where hygiene control may be insufficient. Unpasteurized cheese, milk and other milk products should never be consumed by pregnant women.

In fact, two deadly listeriosis outbreaks in 2014 were linked to soft cheeses. One illness was reported in a pregnancy and one newborn was diagnosed with listeriosis.

How can women protect themselves against listeriosis?

A good first step is to avoid deli foods, unpasteurized milk, juice and cheese, products made with raw eggs and Pâté. And follow basic food safety rules for buying, storing, and preparing foods.

At the grocery store, buy perishable foods such as meats, poultry, eggs, and dairy foods last so they don’t spend much time out of refrigeration. Keep meats and poultry separate from foods that are eaten raw, such as leafy greens and fruits.

Always store perishable foods, including cut fruits and vegetables, in the fridge. Store foods that will be eaten raw away from uncooked meats and poultry to avoid cross-contamination. And cook meats, poultry, and fish within three days of purchase, or freeze it.

When you’re cooking foods, always use a food thermometer or meat thermometer to check the final internal temperatures of beef, chicken, pork, turkey, fish, and egg dishes. Whole cuts of beef and pork (such as chops and roasts) should be cooked to 145°F. Ground beef, veal, and pork should be cooked to 160°F. All poultry, including ground chicken and turkey, should be cooked to 165°F. Fish and seafood should be cooked to 145°F. Cook shellfish such as mussels until the shells open. And cook all dishes made with eggs to 160°F. You can cook hot dogs and luncheon meats (even if they are already cooked) to 165°F.

What is the treatment for a Listeria monocytogenes infection?

Listeriosis in both moms and babies is treated with antibiotics. The antibiotics are often given intravenously (I.V.) and might need to be given over ten days or more; although the number of days of treatment will depend on on well the antibiotics are doing at clearing the infection. Because pregnant women are so at risk for fetal loss if they contract this infection, doctors may treat them with a prophylactic (preventative) course of antibiotics if the woman has eaten food that may be contaminated even before a positive test shows that they are infected. Some patients may need to be rehydrated with IV fluids and may need additional care in a hospital to make them comfortable.

In healthy non-pregnant people, antibiotics might not be needed at all, and treatment will depend on symptoms.